By contrast, the U.S. has one of the weakest genomic surveillance programs of any rich country, Hanage said. "As it is, people like me cobble together partnerships with places and try and beg them" for samples, he said on a recent call with reporters.

Other variant strains were identified in South Africa and Brazil, and they share some mutations with the U.K. variant. That those changes evolved independently in several parts of the world suggests that they might present an evolutionary advantage for the virus. Yet another strain was recently identified in Southern California; it was flagged because of its increasing presence in hard-hit cities like Los Angeles.

The Southern California strain was detected because researchers at Cedars-Sinai, a hospital and research center in Los Angeles, have unfettered access to patient samples. They were able to see that the strain made up a growing share of cases at the hospital in recent weeks, as well as among the limited number of other samples haphazardly collected at a network of labs in the region.

Not only does the U.S. do less genomic sequencing than most other wealthy countries, but it also does its surveillance in a happenstance way. That means it takes longer to detect new strains and draw conclusions about them. It's not yet clear, for example, whether the Southern California strain was truly worthy of a press release.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Vast swaths of America's privatized and decentralized system of health care aren't set up to send samples to public health or academic labs. "I'm more concerned about the systems to detect variants than I am these particular variants," said the director of Nevada's public health laboratory, Mark Pandori, an associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno School of Medicine.

Limited genomic surveillance of viruses is yet another side effect of a fragmented and underfunded public health system that has struggled to test, track contacts and get Covid-19 under control throughout the pandemic, Wroblewski said.

The country's public health infrastructure, generally funded disease by disease, has decent systems set up to sequence flu, foodborne illnesses and tuberculosis, but there has been no national strategy for Covid-19. "To look for variants, it needs to be a national picture if it's going to be done well," Wroblewski said.

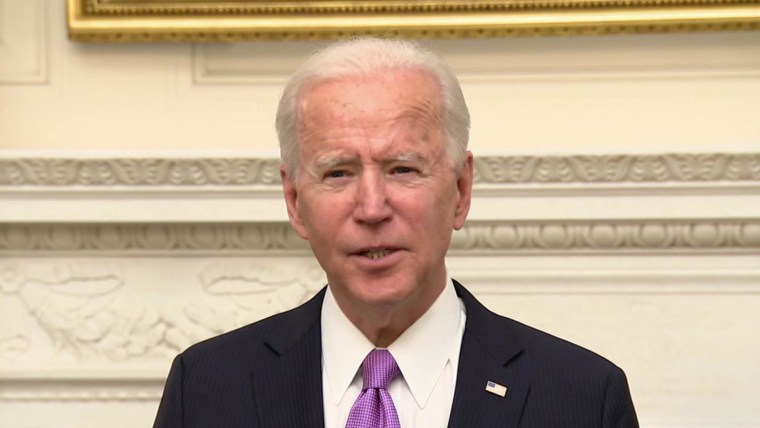

Last week, the Biden administration outlined a strategy for a national response to Covid-19, which included expanded surveillance for variants.

So far, vaccines for Covid-19 appear to protect against the known variants. Moderna has said its vaccine is effective against the U.K. and South African strains, although it yields fewer antibodies in the face of the latter. The company is working to develop a revised dose of the vaccine that could be added to the current two-shot regimen as a precaution.

But a lot of damage can be done in the time it will take to roll out the current vaccine, let alone an update.

Even with limited sampling, the U.K. variant has been detected in more than two dozen states, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned that it could be the predominant strain in the U.S. by March. When it took off in the U.K. at the end of last year, it caused a swell in cases, overwhelmed hospitals and led to a holiday lockdown. Whether the U.S. faces the same fate could depend on which strains it is competing against and how the public behaves in the weeks ahead.

Already risky interactions among people could, on average, get a little riskier. Many researchers are calling for better masks and better indoor ventilation. But any updates on recommendations would be likely to play at the margins. Even if variants spread more easily, the same recommendations public health experts have been espousing for months — masking, physical distancing and limiting time indoors with others — will be the best way to ward them off, said Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, a physician and professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

"It's very unsexy what the solutions are," Bibbins-Domingo said. "But we need everyone to do them."

That doesn't make the task simple. Masking remains controversial in many states, and the public's patience for maintaining physical distance has worn thin.

Adding to the concerns: Even though case numbers have stabilized in many parts of the U.S. in recent weeks, they have stabilized at rates many times what they were during previous periods in the pandemic or in other parts of the world. Having all that virus in so many bodies creates more opportunities for new mutations and new variants to emerge.

"If we keep letting this thing sneak around, it's going to get around all the measures we take against it, and that's the worst possible thing," said Pandori of Nevada.

Compared with less virulent strains, a more contagious variant is likely to require that more people be vaccinated before a community can see the benefits of widespread immunity. It's a bleak outlook for a country already falling behind in the race to vaccinate enough people to bring the pandemic under control.

"When your best solution is to ask people to do the things that they don't like to do anyway, that's very scary," Bibbins-Domingo said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

"What" - Google News

January 28, 2021 at 05:03PM

https://ift.tt/3pqiuKJ

Can the U.S. keep Covid variants in check? Here's what it takes. - NBC News

"What" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3aVokM1

https://ift.tt/2Wij67R

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Can the U.S. keep Covid variants in check? Here's what it takes. - NBC News"

Post a Comment