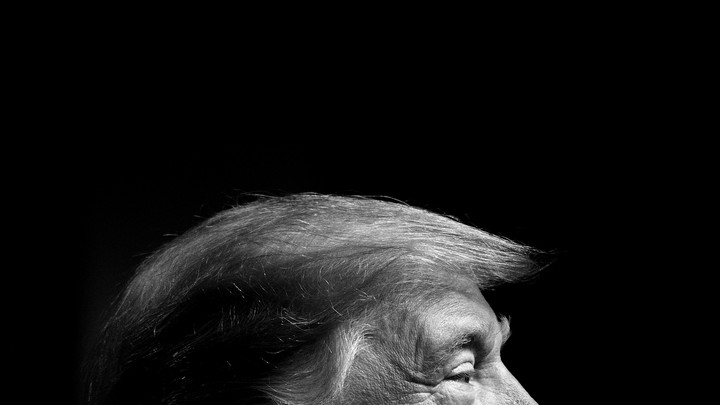

As a White House resident, President Donald Trump is a goner. But his stranglehold on the GOP seems as tight as ever: Three in four Republicans say they believe their man won the 2020 election. Can the GOP channel the energy of his most fervent supporters and advance a sort of Trumpism without Trump? The answer depends on what Trumpism is—a populist prototype, a personality cult, or something stranger.

To some, Trumpism marks the beginning of a new Republican Party. Four years ago, Trump created a coalition that was more blue-collar and less white than the GOP vote in previous elections by combining an anti-immigration and protectionist message with a call to dismantle the sclerotic and corrupt bureaucracy. In 2020, he expanded his working-class base by winning significantly more Latinos, especially in south Texas and Florida. “You can see the foundation of a possible after-Trump conservative majority that is multiethnic and middle class and populist,” the columnist Ross Douthat wrote in The New York Times.

But the UC Berkeley sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild believes that Trumpism is intimately tied—for now at least—to its namesake, because it exists beyond the logic of policy. It exists in the dreampolitik realm of feelings. “If there’s one thing I think the mainstream press still gets wrong about Trump, it’s that they are comfortable talking about economics and personality, but they don’t give a primacy to feelings,” Hochschild told me. “To understand the future of the Republican Party, we have to act like political psychiatrists.”

In her 2016 book, Strangers in Their Own Land, Hochschild went to the Deep South to study an emerging conservative identity and came away with something like a Rosetta stone for the rise of Donald Trump. She offered a psychological allegory for the right-wing worldview, which she called the “deep story.”

The deep story went like this: You are an older white man without a college degree standing in the middle of a line with hundreds of millions of Americans. The queue leads up a hill, toward a haven just over the ridge, which is the American dream. Behind you in line, you can see a train of woeful souls—many poor, mostly nonwhite, born in America and abroad, young and old. “It’s scary to look back,” Hochschild writes. “There are so many behind you, and in principle you wish them well. Still, you’ve waited a long time.” Now you’re stuck in line, because the economy isn’t working. And worse than stuck, you’re stigmatized; liberals in the media say every traditional thing you believe is racist and sexist. And what’s this? People are cutting in line in front of you! Something is wrong. The old line wasn’t perfect, but at least it was a promise. There is order in the fact of a line. And if that order is coming apart, then so is America.

Hochschild tested this allegory with her Republican sources and heard that it struck a chord. Yes, they said, this captures how I feel. In the past few years, she’s kept in touch with several of her connections from the Deep South and keenly tracked their philosophical evolution. She’s watched the locus of their anxiety move from budgets (“They never talk about deficits anymore,” she told me) to the entrenched and “swampy” political class. She also witnessed the Trumpification of everything. “There used to be a Tea Party,” she said. “Now it’s all Trumpism.”

If we want to understand this movement, Hochschild told me, we have to understand what happened in the past five years to the people in the line. “I now see that the line metaphor in my book was only Chapter 1 of the deep story,” she said. “What I’m seeing now is there are more chapters.”

If Chapter 1 was “The Line,” Chapter 2 was “The Arrival.” When Trump appeared to the members of the broken line, Hochschild saw that he embodied the most ineffable aspects of the deep story. Trump might be a lifelong bullshitter, but one thing he has never had to bullshit is his grievance toward liberal elites and his antipathy for the groups whom Tea Party Republicans already knew they hated. He animated their distrust toward Barack Obama with his birtherism claims. He gave shape to their hatred for Hillary Clinton by leading “Lock her up!” chants. “From his first rallies, Trump’s basic message has always been ‘I love you, and you love me, and we all hate the same people,’” Hochschild said.

Lest you think that is a facile interpretation from a coastal interloper, consider this more recent analysis from the GOP political consultant Liam Donovan: “One of the most impressive [and] politically utile things Trump has done from the beginning is get his fans to internalize their support and perceive even a mild rebuke of him [and] his actions as a personal attack on them.” Trump’s unembarrassed embrace of resentment politics made him the messenger of the broken line.

After “The Arrival,” Chapter 3 was “The Suffering”: Trump’s presidency. “A lot of nonreligious liberals can’t tune into the frequency on which Donald Trump is speaking to the right,” Hochschild said. Throughout his term, the president has been laser-focused, not so much on the day-to-day tasks of the job, but rather on calling out his political enemies—the press, the bureaucracy, the far left, the impeachers, the vote-counting software. But although liberals might see pathological anger here, Hochschild’s sources have told her they perceive something deeper than rage. They see suffering. “‘I’m suffering for you,’ is a profound message,” she said. “Suffering consolidates and strengthens belief. It puts an ism to the word Trump and gives a political project the shape of a religious movement.” Perhaps in part because Trump considers himself godlike, he is absorbing the underlying religious paradigm of voters who are seeking some new creed to explain the broken line and mend it.

Now we are in Chapter 4, “The Afterlife.” Since Trump’s political defeat, he and his deputies have asked followers to believe in miracles of escalating fantasy. What began as a simple telegraphed message—that Trump would never accept the results of an election he lost—has become an extravagant mythology, populated with new names and characters: Dominion, Hugo Chavez, international communist plots, illegal ballot dumps, mail-in voter fraud, urban voting irregularities, the Kraken! Trump’s conspiratorial reaction to his election loss is causing the GOP to fissure. On one side is the “Stop the Steal” movement and the majority of Republican voters who say they don’t believe the results. On the other side is a group that largely supports the president but considers the Stop the Steal movement theatrical, at best, and brain-wormed, at worst. Moving forward, Hochschild says, many Republicans will have to choose where they place the balance of their allegiance: Fall-in-Line Trumpism or Fall-Apart Trumpism.

The deep story has always had a whiff of conspiracism: The Tea Partiers thought Obama’s rise to power was fishy, and they were already suspicious about the forward mobility of the back-of-the-liners. But in the past four years, conspiracism has bloomed beneath a president who welcomes any fantasy that makes him its suffering protagonist.

“Conspiracy comes from a place of wanting to understand and master forces that are beyond you,” said Hochschild, who still speaks with former Tea Partiers who have fallen into the maw of QAnon and Stop the Steal. “I hear them justifying their favorite conspiracies,” she said. “They say, ‘Well, I don’t believe that chemtrails are spying on me. I don’t believe that one, but I do believe these over here. They say, ‘I’m not crazy like that, but I do believe this.’” They locate themselves in the conspiracist sphere. And in Trump, they have found the paranoiac in chief of the conspiracist sphere.

Hochschild is telling us that Trumpism is not just a garland of public-policy proposals that any other Republican can drape around his or her neck. And it is more complex than a personality trait, or a talent for saying mean stuff on Twitter. Rather, Trumpism is an emotional planet that orbits around Trump’s star. Breaking the connection between Trump and the better part of the GOP will require either that Trump disappears (an unlikely proposition) or that a larger star emerges from the Republican backbench (also unlikely).

At the end of our conversation, I asked Hochschild what she’s learned from the past four years. “I used to think of political identity as something more solid,” she said. “I now think of political identity as like water that’s always going somewhere, that needs to go somewhere, but where it goes depends on the lay of the land, the rock formations that stand in its way,” she told me. She’s still waiting to see where Trump moves the mountain.

"What" - Google News

December 29, 2020 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/2KYQU7U

What Was Trumpism? - The Atlantic

"What" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3aVokM1

https://ift.tt/2Wij67R

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What Was Trumpism? - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment